When you compare transportation trends in 2019 to the extraordinary results of 2018, this year may seem bleak. For freight brokers, 2019 was more of a good-news-bad-news kind of year. Some brokers are not moving as many loads as they did last year, but others are growing rapidly. The overall impact is an increase of 7% or more in spot market loads moved this year, compared to 2018.

More important, while their shipper customers continue to press for price concessions on freight transportation, brokers have been able to fill even the lower-priced orders without incurring a business loss. That’s because they’re finding carriers who will haul the freight for relatively low rates. So while brokers’ top-line revenues are lower than before, their gross margins remain solid at an average of 16%. With just a little cost-cutting, the DAT benchmark group* of mid-sized brokers maintained bottom-line profitability this year so far.

Have the DAT Broker Benchmark delivered to your inbox every quarter.

When rates go down, brokers’ gross margins tend to go up, and vice versa, enabling the brokers to stay profitable. High rates drive top-line revenues up for brokers, however, because each load costs more money to move. Both combinations of revenue and margin can support operating profits.

How much money are we talking about?

That trade-off between revenues and margins doesn’t pencil out so well when you own trucks. Carriers who are struggling to make a profit this year may find themselves wondering: “How much money does a freight brokerage make on those loads I haul?”

Answer: It’s a little over $75 per load, in a good month.

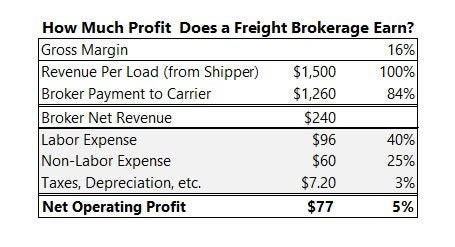

Here’s the math: On a load where the shipper paid the broker $1,500, and the broker’s gross margin matched the Q3 average of 16%, the carrier was paid $1,260. That leaves the broker with $240 to meet payroll and cover rent, utilities, and other expenses, plus a few bucks for Uncle Sam. Way down there at the bottom line, the broker’s net operating profit comes to $77 on that $1,500 load.

“That’s all I have in the load”

When volume and rates drop at the same time, which happened in 2016, the average net profit per load can quickly fall below $40. In some months, the net profit can become a net loss. So when a freight broker says “that’s all I have in the load,” it could be painfully true.

If you own a truck or a for-hire fleet, however, that kind of response can be very frustrating. Conditions for trucking companies have been especially challenging this year. Carriers’ costs are going up — a recent study said operational costs have risen 7.7% this year — just as they are taking in less revenue. This last increase drove costs up to an average of $1.80 per mile (including driver compensation) which means some roundtrips will just barely cover costs. That makes it more important than ever to reduce deadhead, out-of-route miles, and unpaid detention time.

A non-asset freight broker doesn’t have to deal directly with truck payments, maintenance, driver safety, or those other vehicle-related things that keep fleet owners awake at night. But brokers do have a responsibility to pay employees, landlords, and creditors — including carriers — and to make those payments on time. Sometimes, the broker has to rely on a line of credit, because the customers paid late. In those cases, the broker is essentially acting as a banker as well as a matchmaker and a sales agent.

Both carriers and brokers face business risk. At the same time, the two groups depend on each other for success. Go for the win-win.

* Note: Data for the DAT broker benchmark report is drawn from the TMS systems of nearly 100 freight brokers and 3PLs with average 2018 revenue of $13.8 million, a 16% increase compared to 2017.